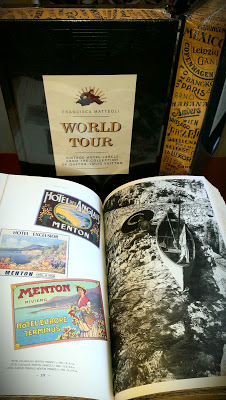

To our surprise the author of that very book, Francisca Matteoli, saw our blog and contacted us to thank us. Francisca is an travel author, journalist, and blogger who lives in Paris. Her previous book Escape: Hotel Stories is another gorgeous book highlighting the passion of travel.

Francisca answered some questions about her new book and about being an avid traveller.

Here's what she said to us.

PP: The Gaston-Louis Vuitton Hotel Label collection is the genesis of your book World Tour. How did you gain access to the collection?

PP: The Gaston-Louis Vuitton Hotel Label collection is the genesis of your book World Tour. How did you gain access to the collection?FM: I was having lunch with Julien Guerrier, editorial director at Louis Vuitton, and I told him about my Chilean great-grandfather and my family who always lived in hotels, and about our life in Chile and France. He then told me that Louis Vuitton had a magnificent collection of hotel labels and that we could connect our stories. He knew I liked writing stories and we thought that it would be a very original way to talk about travel. That is how it all began.

PP: Much of the research about the origin, design and purpose of hotel labels in the book was done by you and not just sourced from the collection. Did you approach the history from a design or travellers' point of view?

FM: The traveller's point of view. As all South Americans, I adore telling stories. And writing stories. My favourite hotel labels bring back many personal memories such as the Hotel Gloria in Rio de Janeiro for example, because I lived in Rio and because it's situated in one of the most legendary cities of the world. I also like very much the label of the Hotel Le Meurice in Paris because it epitomises for me French elegance of a city I love. The label of The Grand Hotel d'Angkor is another of my favourites. It's more a painting than a label. I wanted to bring an emotion when you look at those labels that makes you think "I'd love to go there, to see that place".

PP: Hotel labels have had many a renaissance in their design over the centuries. How important do you think the hotel label is in leading design in other areas or do you think it was a follower?

PP: Hotel labels have had many a renaissance in their design over the centuries. How important do you think the hotel label is in leading design in other areas or do you think it was a follower?FM: A lot of labels in the book are from a period characterized by optimism and peace in Europe. When Paris was decadent and beautiful, with the building of the Eiffel Tower, the Opera Garnier, the Gare d'Orsay, the Grand Palais, the grand hotels. There was a desire of new and extraordinary things. In fact, hotel labels have accompanied all the important art periods and movements.

PP: There are 21 stopovers in the book including destinations from Saint-Raphael to Monaco, Libya to Israel, Mexico to Uruguay . Are these based on real journeys people would have taken over the past couple of centuries?

FM: Yes, absolutely. I wanted to write real travel stories when travel was associated with comfort, luxury, adventure and mystery. A time when people were proud to show the stickers on their suitcases, to discover new places and live adventures. I remember when I came from Chile to France with my family we took a ship and did a travel that lasted 3 weeks - with our luggage, trunks and even some pieces of furniture. It was not only a travel, but also an incredible adventure. Strange, epic, tragic, crazy. I wanted to feel all that again and make the readers feel those emotions too.

PP: The combination of pictures, quotes and vintage labels collected together in World Tour is incredibly evocative and romantic. Was that your intention?

FM: Yes. My family knew the golden age of travel, the steamer-trunks, the luxury liners, an age of elegance. It was an age of hopes and dreams and of people settling into a new country. A time when everything could arrive.

PP: You have written for National Geographic and have also published other books about travel? How did you come to be a travel writer and what is your favourite part about your job?

FM: Well, I've always been surrounded by travellers. And also by adventurers. My Scottish mother and my Chilean father were also driven by an intense curiosity. So like everyone I think, I have been influenced by my background and as I come from South America where everyone likes to tell stories, it was kind of natural for me to mix stories and travels. I published some stories for magazines but I really started to write seriously after I went to Rwanda with the French Doctors and did a story for National Geographic. I wanted very much to write something about this experience, so I went to see the editor of the magazine and asked him if he was interested in a story. I had never written for such an important magazine before. I knew that very few people had been to Rwanda in those conditions and had the opportunity to see the country from that angle, and I felt that it was going to be a once in a lifetime experience. The editor of National Geographic said he was interested in a story, he asked a photographer from Magnum agency to join me, and that is how I started writing real travel stories. That was my first real work as a travel writer.

FM: Well, I've always been surrounded by travellers. And also by adventurers. My Scottish mother and my Chilean father were also driven by an intense curiosity. So like everyone I think, I have been influenced by my background and as I come from South America where everyone likes to tell stories, it was kind of natural for me to mix stories and travels. I published some stories for magazines but I really started to write seriously after I went to Rwanda with the French Doctors and did a story for National Geographic. I wanted very much to write something about this experience, so I went to see the editor of the magazine and asked him if he was interested in a story. I had never written for such an important magazine before. I knew that very few people had been to Rwanda in those conditions and had the opportunity to see the country from that angle, and I felt that it was going to be a once in a lifetime experience. The editor of National Geographic said he was interested in a story, he asked a photographer from Magnum agency to join me, and that is how I started writing real travel stories. That was my first real work as a travel writer.My favourite part about my job is the fact that I have the chance to see life from so many different angles. Life is a kaleidoscope. We never get to see all the colours or all the sides because they are changing all the time and we are changing too. But it's so exciting to try to catch the most of it, no? One of my biggest reward as a travel writer is being able to change the false impression that somebody has on a country and people.

PP: Who do you think will be interested in reading World Tour?

FM: Everybody! People of all ages and all kinds who want to travel or to dream, to live adventures, to see unexpected things; beautiful, moving, funny, special, to read stories which make us love the world where we live.